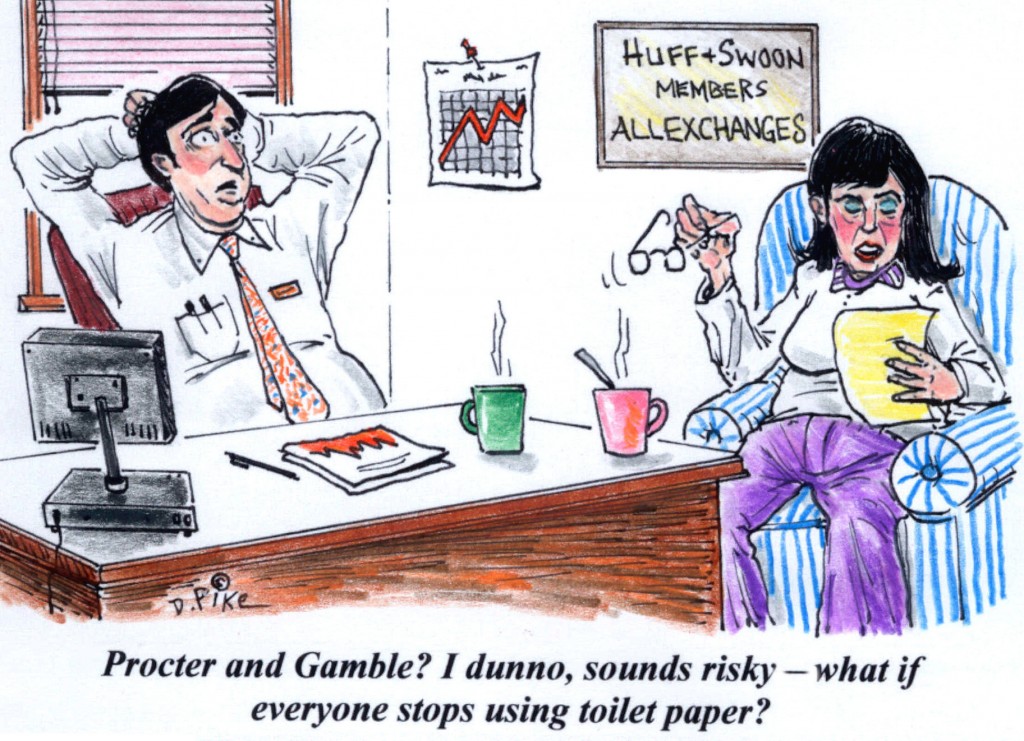

(Cartoonist: Doug Pike: Cartoonstock.com)

Risk is a four letter word which is commonly used in the markets. When investors decide to invest in equities as an asset class they are taking a higher risk. The risk premium is what they earn for taking that risk. Also within equities as an asset class, riskier stocks should deliver higher returns as compared to safe ones (in the longer term). This is common sense and the cornerstone of market-theory. If this were untrue, why would investors invest in high risk securities? In reality, the opposite is occurring.

Risk, Fund management and Benchmarking.

Simply stated, a benchmark is an investing lifeline. It is a barometer against which a fund managers performance is compared. In our markets the Nifty is the market benchmark. If a fund manager has provided returns in excess of the Nifty, there is out performance and vice-versa. Needless to say all the fund managers are trying to beat the Nifty. The period of measurement is generally one year.

A word about fund management as it exists in the current scenario. There has been a change in the investor behaviour since the last bull run in 2008. Today most investors prefer the fund route to investing in stocks, rather than the direct route. In the fund space there can be active and passive funds. The active funds are managed ‘actively’ meaning that they are trying to beat the benchmark. The passive funds are just a replica of the benchmark and track the benchmark. Hence passive funds are more or less same as an index fund. In this post, when I am referring to funds managed, I am specifically talking about the active fund space (including Portfolio Management – PMS).

Risk and active fund management

I attended a Morningstar Investment conference some days back. Morningstar is one of the leading providers of independent investment research. They cover the fund universe and their ratings are sought after. As part of the two-day conference there were various ’round table’ sessions with India’s leading fund managers. One of the fund managers happened to mention that ‘higher the risk higher the return’ is an anomaly and in fact it is the reverse. Since the fund manager in question was one who I have an immense respect for, it got me thinking as to why and how he must have said what he did. Surely he could not make a faux pas? I got the answer in a new paper, dated September 13, 2014, called ‘Asset Management Contracts and Equilibrium Prices’ by Andrea M Buffa, Dimitri Vayanos and Paul M Woolley. The salient points are:

-

Managers are unwilling to deviate from the index and this exacerbates price distortion.

- If managers trade against over valuation their chances of deviating from the index are higher. Hence fund managers prefer to trade with the over valuation than to trade against it. This effectively increases the volatility of the overvalued asset.

- This results in price distortions and inefficient pricing in markets.

- Performance relative to benchmarks determines managers compensation and also the funds that they get to manage. Hence managers are unwilling to deviate from the benchmark.

- This results in distortions whereby the undervalued assets become cheaper and over valued assets become more expensive. It seems that, in the current scenario the positive distortions, dominate thereby biasing the aggregate market upward.

- The higher the market goes the lower the expected future return.

- The over valued assets account for a larger portion of market movements than the under valued assets.

- Managers prefer to trade with the inherent systemic biases. Hence practically none of the managers short over valued assets and buy under valued assets, which in fact is the correct thing to do.

- This effectively results in one-sided moves. The volatility of the over valued assets increases.

- Hence the negative relationship between risk and expected return.

-

Ideally to provide value to the investors the manager must over-weight the under valued assets and under-weight the over valued assets. In this way he can add value over the index.

I think the above hits the nail on the head. In the current scenario mis-pricing of assets is rampant and practically no fund manager takes any corrective action. This in fact increases the risk in the market as a whole. In layman’s terms the implications of the above are as follows:

1. The study suggests that the relationship between risk and return has been distorted due to the practice of bench-marking by fund managers. This is due to the way money is invested. In the olden days allocations to equities were done by individuals, now they are done by institutions. These institutions use bench-marking. Their performance is measured against a benchmark. If they outperform well and good. If they under perform they face the heat. Effectively bench-marking exacerbates the herd mentality. Hence ‘equity research’ has become an echo. This results in a spiralling of valuations beyond justifiable levels. So if one manager gives a buy call multiple managers follow and vice versa.

2. If an investor wanted index like returns, he would be happy buying the ETF (Niftybees) or putting money in a low-cost index fund. For investors who want to earn better than index returns, the question of approaching a fund manager does arise. In all such cases, the fund managers are under an unwritten obligation to outperform the index returns. In fact, in most cases their compensation depends upon their out performance. In such a scenario, where all the managers are in a mad chase for returns, they obviously end up buying the same set of stocks (more or less). Hence the terminology of ‘underweight’ and ‘overweight’ instead of ‘own’ and ‘do not own’.

3. The following illustration will help understand what I am trying to say:

-

Suppose a manager is underweight INFY which has a weight of (around) 7.00 % in the Nifty. Suppose in his portfolio the weight age is 3.5 %

- If the market price of INFY doubles it has an unintended consequence. In the manager’s portfolio it’s weight has halved. So for favourable sectors the manager would be well advised to be equal weight or over weight in INFY.

- Now consider the sectors which are out of favour. DLF has a 0.20 % weight age in the index. If a fund manager is over weight (or double-weight) in DLF, and it’s price halves (which it almost did), it has the reverse effect on the fund returns. In other words the NAV of the fund would fall by twice the percentage of the fall in DLF.

- This is just an example and not investment advice or bias. Effectively, bench-marking gives managers a huge incentive to stay fully weighted in large index heavy weight stocks. This inverts the risk and return concept. Hence, the old paradigm of higher the risk higher the return has been upended. Now it is, higher the risk lower the return.

4. When the market as a whole is involved in this kind of euphoria, we have a situation like the year 2000. Then Satyam Computers was Rs. 7000 and State bank of India was Rs. 200. Those investors who were contrarian in those days, have made much more than the ones who chased technology. In today’s scenario, if a manager were not to invest in the ‘hot’ stocks, he will have had to return all or most of his money, or face massive under performance.

5. This, in my opinion, is a wrong way of allocating capital. This does throw up the kernel of an opportunity for the layman investor. How?

- Investors must be rewarded for taking more risk, which they are taking by choosing to invest in the equity markets. Many managers are told to maximize their out-performance and minimize the volatility of that out-performance. The fund management universe is unwilling to take calculated risks in their investment process. They end up buying over valued assets, leaving the under valued ones languishing.

- Hence it is possible for investors to take advantage of flawed logic which fund managers have to follow. The maths of that pushes managers to buy shares with high beta, those that rise and fall faster than the market. Less volatile shares are less appealing, making them cheaper – meaning they can provide higher returns to those not constrained by a benchmark. It throws up opportunities to buy stocks which are out of favour, and where the stop-loss is far narrower.

Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital on Risk

Howard Marks is a contemporary investing guru. In a note he circulated to his clients titled “Risk Revisited” he says:

-

On fundamental risk and valuation risk: “The two main reasons for an investment to be unsuccessful are fundamental risk (relating to how a company or asset performs in the real world) and valuation risk (relating to how market prices that performance). Efforts to reduce fundamental risk by buying higher-quality assets often increase valuation risk, given that higher-quality assets often sell at elevated valuation metrics”.

-

On volatility : He says “Volatility is a measure of risk. Actually nobody fears volatility. What they fear is risk, in effect a permanent impairment of capital. Investors can ride out of volatility but it is next to impossible to recover from a permanent loss of capital. The probability of loss is no more measurable than the probability of rain. In order to achieve superior results, an investor must be able – with some regularity – to find asymmetries; instances when the upside potential exceeds the downside risk. That’s what successful investing is all about. Investments that seem riskier have to appear likely to deliver higher returns, or else people won’t make them. Hence as risk increases : the expected returns increase, the range of possible outcomes become wider and the less-good outcomes become worse. Hence riskier investments are ones where the investor is less secure regarding the eventual outcome and faces the possibility of faring worse than those who stick to safer investments, and even of losing money. These investments are undertaken because the expected returns are higher”.

I think the above pretty much says it all.

Conclusion

The increase in institutional ownership of Indian equities has resulted in the markets being very clearly in danger of running a valuation risk. There is a mad institutional rush to participate. In the olden days the retail Gujarati investor used to say હૂન રહી ગયો (hoon rahi gayo) – I am left out. This means that in case one does not participate, one will be left out of the opportunity to make a fast buck. This was however restricted to the retail investors. Now the retail investors are pouring money in to the fund space. The fund managers are behaving in exactly the same way as the retail investor of yore. The only difference is that with the international exposure to Indian markets there is a new term. Instead of હૂન રહી ગયો, we now have FOMO – the Fear Of Missing Out. This is likely to continue to drive markets in the immediate term.

A v good article. The expectations of higher returns,I suppose, are generated by an investor , by looking at the history of the asset class & not from any Financial theory. So his expectation of Higher returns with higher risks is generated by his own investing history & his own experiences with the particular asset class . We all know that, most of the financial markets do not behave exactly as per any theory , so the reliance on own experience should be prime, rather than any theory, while taking an investment decision.

True. It is past experience that dictates expectations as you have correctly pointed out

Since your article(today’s) is based on conceptual analysis…kindly note that the principle is NOT about receiving higher returns given higher risk……..Financial Theory actually says the following…HIGHER THE RISK HIGHER THE EXPECTATION OF RETURN….Actual returns do not necessarily remain highly correlated to Risk …

So it is important to understand how expectations are built and examined in Finance Theory and by Practioners…..

Maybe you could attend another Investment seminar (preferably at FLAME) and then share your learnings

Why would any one venture in to equities otherwise. I am concerned with the practical aspect of investing. The theory part you may be correct.

Unfortunately I cannot afford courses at FLAME. They are outside my budget. They are meant for the institutional investors or their progeny. The day you announce a big discount for the needy, I will be the first to enrol!!

Interesting article. However, I would have been happy to get advice about how an individual should act now. Is it better to invest on your own to get high returns or join this herd of retail investors and get safe returns?

I think as an individual investor buy the good stocks in the battered sectors. The commodity and real estate sectors are heavily battered. However within these you will have to be very very stock specific