Are we are investing in a loose collection of individual stock names or a monolithic stock market? What would happen to the different stock prices that are not part of the benchmark composition if the benchmark indices were to correct?

To answer this question, one needs to understand the difference between the terms ‘a market of stocks’ and ‘a stock market.’ There is a school of thought that says that since it is ‘a market of stocks,’ individual stock prices outside the benchmark composition would be unaffected. The counter-argument is that, since we are investing in the stock market as a whole, any correction in the benchmark indices would result in a broad-based correction that would affect a majority of the listed stocks.

Market of Stocks or a Stock Market

Those who argue that this is ‘a market of stocks’ advocate the following:

- Individual investors investing results depend solely upon what happens to the individual stocks that he or she owns, talking about the market as a whole is a grand waste of time.

- Everyone is investing for the long-term. Hence, the distribution of returns does not matter. In any case, the distribution of stock market returns does not follow a standard curve. As a result, even if there were to be a correction, stock prices would bounce back over the medium and long-term. Net-net, valuations don’t matter.

- It is a stock-pickers market; one in which the correlations between different stocks is very low. Hence, as long as we can pick the correct stocks to invest in, the benchmark indices can go to hell (and back) in a handbasket, it wouldn’t matter.

I don’t agree with any of the above. I think it is (and has always been) ‘a stock market’ that we are investing in, and not ‘a market of stocks.’ What are we trying to establish is: how correlated are individual stock prices with each other? I have tried to answer that question, without getting into the esoteric world of correlation coefficients. My thoughts:

- There are phases when a vast majority of stocks are correlated to one another, and at times, these correlations seem to break down. In my opinion, it would depend on when we are asking the question; the answer would change accordingly. However, pinning down correlation coefficients with any degree of accuracy and on a consistent basis, then using them to generate alpha, is next to impossible.

-

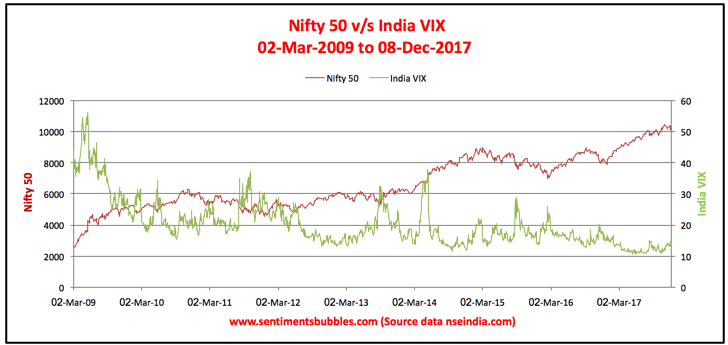

Over the long-term (the only term that matters), stocks have always been correlated with each other. But the correlation between stocks tends to swing with the Volatility Index. When Volatility is high, correlations tend to move higher and vice-versa. Increased Volatility translates into lower stock prices, and historically correlations have been higher when prices are moving lower than when they are running higher. That is evident from the image shown below.

-

Historically, when benchmark indices correct by ‘x,’ individual stock prices tend to correct by a greater multiple; sometimes as much as two to three times the benchmark correction. I don’t subscribe to the view that ‘this time it’s different’; it never is.

-

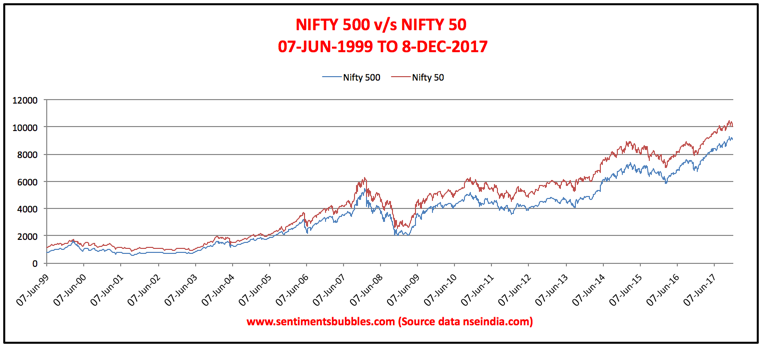

I will concede that stock picking matters. But it is wrong to assume that the ‘good stocks’ will continue to rise forever. The image shown below compares two benchmark indices, Nifty 50 and Nifty 500. One consists of 50 stocks and the other consists of 500 names. If it were not a stock market but a market for stocks, these images wouldn’t have looked so similar. They should have diverged significantly. The two indices are in lockstep with each other.

To conclude, just because the stock market has been rising for the past twelve months does not mean that it will continue to do so. The higher the market climbs, the lower will be prospective future returns and the greater the need to exercise caution.

Valuations – TINA & Performance Chasing

There are those who believe retail investors have no alternative but to invest in stocks – TINA (There Is No Alternative). TINA is being interpreted to mean that the Mutual Fund Schemes will continue to get robust inflows. Hence, the assumption that when the markets do correct, swarms of buyers would emerge out of the woodwork and immediately buy any and every dip. Why? Because of TINA. Flows are positively correlated with the current market prices. Hence, we seem to have come to a situation where the flows matter more than the valuations of the individual stocks.

Is there an optimum level at which the Nifty should trade? A particular level at which all participants would agree that this is indeed the ‘perfect valuation.’ Has there ever been such a perfect stock market level? Never, neither will there ever be. The market is trying to establish one by trial and error.

The valuations exercise is based on estimates of expectations of future earnings. Change the estimates and the underlying assumptions; one will end up in a new galaxy altogether. Whichever way one wishes to interpret the valuation puzzle, there is no doubt about the fact that valuations are stretched. Should one then conclude that valuations have ceased to matter? I think they have, but those two are tautological statements. My reasoning is as follows:

- Are money managers investing because they can identify mispriced assets that they find to be relatively cheap? I don’t think so. It’s more the case that inflow of investable funds far exceeds the opportunities that are available. In such a situation the money manager is faced with a Hobson’s choice. He or she either has to has to (a) stop accepting fresh funds and risk underperformance or (b) accept the inflow and invest the money somewhere. No prizes for guessing what he or she chooses.

- Underperformance on the part of a money manager would translate into money being taken away from him or her, and given to the one who performs. The immediate fallout is, asymmetrical herding in the way money is being put to work. Most money managers own (almost) the same set of stocks (the weight varies). As a result, most of the outperforming stocks are ‘over owned.’ Effectively, all the managed portfolios are pointing in the same direction.

FOMO, the fear of missing out and our innate desire to keep up with the Joneses, seems to result in robust inflows of managed money. In the current environment, even the money managers want to keep up with the Joneses, and that accentuates the problem. FOMO has a direct fallout and does result in performance chasing. In fact, ‘performance chasing’ is visible in the world of Mutual Fund Investing. A Bloomberg article titled, Indian Mutual Funds Now Manage 20 Lakh Crores seems to attribute the inflows to ‘maturity’ among retail investors. I interpret it as ‘high expectations’ and ‘performance chasing.’ I think investors forget that performance chasing never ends well. In their ‘prepared remarks,’ money managers seem to reiterate time and again that valuations are stretched. Despite this, there are no sell calls. Why is that? They prefer to interpret the ‘performance chasing’ as a ‘tsunami’ and expect an even more significant inflow of funds in the immediate future.

The ability to sell is something over which all of us have absolute control. However, we seem to have developed expectations for the future that are at a magical level. Hence, instead of utilising something over which we do have control (our ability to sell), we seem to be attempting to alter our interpretation of the facts (over which we have no control), to make them consistent with the desired outcome. Among statisticians, there is a saying that ‘if one tortures the data long enough, the data will confess to anything. ‘ Something similar seems to be happening in the marketplace. As a result, we seem to be afraid of selling. Greed and Fear have given way to Hope and Fear. The fear that prices will climb higher after we sell, and the hope that they indeed do so rise, once we decide not to sell. Tellingly, many a sell decision is being postponed or put on hold by using the words, ‘Lets give it another day.’