Important Cognitive Biases

There are many known biases that can hurt returns; these biases affect every human being and there are zero exceptions. At the same time, there isn’t any shortage of free advice about how to recognize and combat these biases. The advice so offered does lead some of us to believe that we can escape the impact of Cognitive Biases by behaving in a certain way. The reality is a bit nuanced. Being aware of these biases is of paramount importance. Accepting that we cannot escape from them is equally critical. Anyone who thinks that he or she is immune from bias is fooling himself or herself as the case may be. While investing it pays to accept your biases and put in place ‘systems’ to minimise their impact. The most important Cognitive Biases are highlighted below.

Mental Accounting

Mental Accounting refers to our inclination to categorize and handle money differently, depending upon:

- Where it comes from

- Where it is kept

- How it is spent

The idea of mental accounting was introduced by Richard Thaler.

The Man with the Green Bathrobe

There is a book called ‘How Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes’ by Gary Belsky and Thomas Gilovich. The following is extracted from the book (emphasis is mine):

By the third day of their honeymoon in Las Vegas, the newlyweds had lost their $ 1,000 gambling allowance. That night in bed, the groom noticed a glowing object on the dresser. Upon inspection, he realized it was a $ 5 chip they had saved as a souvenir. Strangely, the number 17 was flashing on the chip’s face. Taking this as an omen, he donned his green bathrobe and rushed down to the roulette tables, where he placed the $ 5 chip on the square marked 17. Sure enough, the ball hit 17 and the 35–1 bet paid $ 175. He let his winnings ride, and once again the little ball landed on 17, paying $ 6,125. And so it went, until the lucky groom was about to wager $ 7.5 million. Unfortunately the floor manager intervened, claiming that the casino didn’t have the money to pay should 17 hit again. Undaunted, the groom taxied to a better-financed casino downtown. Once again he bet it all on 17—and once again it hit, paying more than $ 262 million. Ecstatic, he let his millions ride—only to lose it all when the ball fell on 18. Broke and dejected, the groom walked the several miles back to his hotel. “Where were you?” asked his bride as he entered their room. “Playing roulette.” “How did you do?” “Not bad. I lost five dollars.” This story has the distinction of being the only roulette joke we know that deals with a bedrock principle of behavioral economics. Indeed, depending on whether or not you agree with our groom’s account of his evening’s adventure, you might have an idea why we considered a different title for this chapter: “Why Casinos Always Make Money.” The usual answer to that question—casinos are consistently profitable because the odds are always stacked in management’s favor—does not tell the whole story. Another reason casinos always make money is that too many people think like our newlywed: Because he started his evening with just $ 5, he felt his loss was limited to that amount. This view holds that his gambling winnings were somehow not real money—or not his money, anyway—and so his losses were not real losses. No matter that had the groom left the casino after his penultimate bet, he could have walked across the street and bought a brand-new BMW for every behavioral economist in the country (and had enough left over to remain a multimillionaire). The happy salesman at the twenty-four-hour dealership would never have asked if the $ 262 million belonged to the groom. Of course it did. But the groom, like most amateur gamblers, viewed his winnings as a different kind of money, and he was therefore more willing to make extravagant bets with it. In casino-speak this is called playing with “house money.” The tendency of most gamblers to fall prey to this illusion is why casinos would make out like bandits even if the odds weren’t stacked so heavily in their favor. The “Legend of the Man in the Green Bathrobe,” as the above tale is known, illustrates a concept that behavioural economists call “mental accounting.” This idea, first proposed by the University of Chicago’s Richard Thaler, underlies one of the most common and costly money mistakes: the tendency to value some dollars less than others and thus waste them. More formally, mental accounting refers to the inclination to categorize and handle money differently depending on where it comes from, where it is kept, or how it is spent.

All of us do something similar when we are gifted money on our birthday or we get a tax refund or with any windfall gain that we receive.

The Pain of Paying

We experience the pain of paying whenever we are required to settle our bills. Each of us suffers it in different degrees, depending upon whether we are stingy or a spendthrift. This bias is a directly related to the fact that we are Loss Averse.

Confirmation Bias

It doesn’t take much for any of us to believe something. Once we have formed our belief, we tend to protect what we think. Confirmation Bias is the human tendency to search for, interpret and remember information in a way that confirms one’s pre-existing beliefs. We tend not to change our behaviour, even though the fresh evidence may, in fact, be contradictory to our opinions. We look for evidence that confirms our prior beliefs. In this way we aggravate our bias. When we are confronted with evidence that contradicts our beliefs, we have two choices: (a) change our opinions or (b) ignore or even discredit the new information. Nobody likes to be wrong, hence most of us choose (b). Moreover, any information that contradicts our beliefs is an assault on our ego, and we work hard to swat it away. If new evidence aligns with our pre-existing beliefs, we lap it up.

There are two commonly believed fallacies regarding Confirmation Bias, these are:

- Many of us tend to believe that Confirmation Bias happens only to others and not to us. Each of us suffers from Confirmation Bias, and for the most part, we are not aware that our inherent bias is active. We are under the mistaken impression that we have our Confirmation Bias under control, and more often than not we are wrong.

- It has been proved that our Intelligent Quotient (IQ) is positively correlated with the number of reasons that people find to support their side of the argument. In other words, individuals with high IQ’s are more susceptible to Confirmation Bias than those with low IQ’s.

Effects of Confirmation Bias

Cognitive Bias results in the following:

- It encourages homogeneity of thought and leads to poorer decision-making.

- We tend to gravitate towards others with similar viewpoints as ours and this happens even to lawyers, judges and scientists.

Remedies to Confirmation Bias

Just by being aware of one’s biases does not ensure that we can overcome them. The only way to escape from Confirmation Bias is by being actively open-minded. Being actively open-minded means looking out for and seeking diverse viewpoints and dissenting opinions. In other words, encourage viewpoint diversity. Viewpoint diversity is a situation where each person’s views act as a solution to someone else’s Confirmation Bias. Viewpoint diversity is the most reliable way to get rid of Confirmation Bias. Being mindful instead of being mindless is what it is all about. The Ted talk embedded below, teaches us how we can address our Confirmation Bias in a systematic manner.

Filter Bubbles

Eli Pariser coined the term Filter Bubbles in his book of the same name, published in 2011. Filter Bubbles are defined as: a phenomenon in which a person is exposed to ideas, people, facts, or news that adhere to or are consistent with a particular political or social ideology. He used the term Filter Bubble to describe the process of how companies like Google and Facebook use algorithms to keep pushing us in the direction that we are already headed. By collecting our search and browsing data as also our contacts, the algorithms can accurately predict our preferences and feed our Cognitive Biases. We would be better off, without the constant nudge that these algorithms tend to provide. Effectively, a substantial number of internet users are in Filter Bubbles. Is there a way out? In Alex Edmans TED talk (embedded above), he has given some ways in which we can combat our Confirmation Bias. Once we use the methods outlined, the probability of our being engulfed in a Filter Bubble is significantly reduced.

Types of Filter Bubbles

Broadly, there are four types of Filter Bubbles, these are:

- Type 1: Created by audience measurement. Under this type, a measure of popularity is produced based on the number of user views, number of downloads or number of ‘likes’. The calculation is independent of the content.

- Type 2: Created by hyperlinks. Hyperlinks are used as a proxy for authority. For example, research reports produced by some organisation called ‘Centre for…’. We generally tend to be fooled by these kinds of hyperlinks. Another source of authority is the search engine itself. Google is the dominant search engine; many users do not even know that other similar products exist. However, less than ten per cent of the users visit the second page of the search results. Moreover, we tend to trust the search results implicitly. Just because a link appears at the top of our results, it does not mean that the information contained therein is accurate.

- Type 3: Created by social gatekeepers (influencers). Feedback mechanisms on social media sites like Facebook, Twitter and Snap, proliferate the creation and spread of Filter Bubbles. In fact, in today’s internet-connected world, most of the Filter Bubbles emanate from social media websites.

- Type 4: Created by one’s behaviour. Buying a book on Amazon or watching a movie on Netflix, we get suggestions for the next book we might want to read or an upcoming film we might want to view. The bots and algorithms take over our decision-making function drawing us into a Filter Bubble of our own making.

Eli Pariser on Filter Bubbles at TED

Motivated Reasoning

The single largest drawback of Filter Bubbles is that it has encouraged motivated reasoning. In fact, the proliferation of motivated reasoning has made us soft targets in the world of online marketing. What is Motivated Reasoning?

Once we are in a Filter Bubble, we refuse to update our beliefs, or we are not led down that path (due to algorithms). As a result, we fail to update our priors; once an opinion is lodged, it becomes difficult to dislodge. As our pre-existing beliefs decide how we process information, these beliefs get strengthened, and since we are not looking for disconfirming evidence, our bias feeds on itself forming a vicious circle. In this way, our beliefs take on a life of their own, and our confirmation bias draws us more and more into our echo chamber. Once we are in our echo chambers, we assume that everyone else thinks like us; we are blind to the fact that our beliefs might be wrong. This irrational, circular information processing pattern is called motivated reasoning. In other words, informing and updating our beliefs has an undesirable snowballing effect on our cognitive function and our decision-making capability.

Confirmation Bias v/s Desirability Bias

Confirmation Bias and Desirability Bias are often conflated. There is a thin line that differentiates the two. Confirmation Bias is our tendency to see what we expect to see. Desirability Bias is wishful thinking: we see what we want to see. We can take almost any scenario and produce a soothing interpretation of it; wishful thinking is very compelling and also very common. We tend to seize upon what we hope to see as the desired outcome of an event and not on what we expect to see. Desirability bias ensures that we ignore unwelcome evidence completely. Effectively, desirability bias is stronger than confirmation bias. Wishful thinking about favourable outcomes is a form of optimism, and it has its rightful place in the world of business, marriage and a host of other noble vocations. But, when wishful thinking starts ignoring the data and the evidence, it becomes a bias.

Case Study on Confirmation Bias – Theranos

In 2003, Elizabeth Holmes dropped out of college and founded a Theranos. It was touted as a medical technology company. Holmes promised to revolutionize health care with a device that could test for a range of conditions using just a few drops of blood from a finger prick. Holmes, who used to dress like Steve Jobs, was an attractive blonde and she managed to capture the imagination of many big-name investors. Theranos was valued at $9 billion, with a shareholder roster that boasted of the ‘whos-who’ of corporate America.

The story was too good to be true. John Carreyrou, an investigative journalist of the Wall Street Journal reporter exposed the $9 billion startup as a fraud. He went on to write a book on the expose, called ‘Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup’.

Overconfidence

The humorist, Josh Billings has said:

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

The more you know, the more you will think you know more even more than you do. The road to investing hell is paved with overconfidence. In the current scenario, investing in Mutual Fund Schemes has been very popular over the last couple of years. It is a fact that the bulk of the turnover on the bourses results from trades executed by institutions. Of these institutional trades, Mutual Fund Schemes account for a significant portion. Research conducted on the ‘portfolio turnover’ (which is defined as how much each Mutual Fund Scheme has churned its portfolio over the past twelve months) has been an eye-opener from the viewpoint of Behavioral Investing. While almost all fund managers speak of the benefits of long-term investing, very few of them, practise what they preach. Typically, a turnover ratio of 100 per cent is said to be high. A turnover that is greater than 100 per cent signifies that the fund manager has churned the entire portfolio. There is no consensus on what an ideal turnover ratio ought to be; needless to say, the lower the portfolio turnover, the better. Portfolio Turnovers are known to be high, and they stay high. The reason being, overconfidence bias among fund managers. Most of what is being bought and sold constitute mindless activity being conducted by overconfident investors. Moreover, the churning of portfolios occurs even though there is practically no change in the underlying odds. It goes to show that, overconfident investors tend to engage in mindless buying and selling activity. The ‘Portfolio Turnover’ metric highlights the overconfidence of the money managers and also their ‘Action Bias’ (which has been explained a little later in this chapter).

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: we are all confident idiots

One of the most fundamental characteristics of human nature is to think that we are better than we actually are. There is an inner con man within us and that inner con man is a big fat liar. Most of us think that as compared to the averages, we are better looking, better investors, better savers, better lovers, better drivers etc. Just remember that mathematically, when we talk in terms of averages, half the people will be below average and the other half will be above average. Yet, we find that roughly 75 per cent of us think we are above average in any given skill or task. Thats ‘overconfidence bias’ and in the world of investing, it inevitably lands us in trouble. Being overconfident is not all bad; Kahneman says, ‘the combination of optimism and overconfidence is one of the main forces that keep capitalism alive’. If all of us were realistic and not overconfident and ambitious, we would never take any risks and there would be no innovation. Positive thinking is essential and must be practised at all times. However, in life as in investing, things are not just either black or white. There are shades of grey. Incidentally, Kahneman is known to have publicly said that he does not invest in equities since he is a pessimist.

As investors overconfidence and underperformance are positively correlated in the following ways:

- One of the features of our confidence bias is that it has been shown that commitment increases our confidence levels. In other words, the moment we place the bet, the act of putting down money makes us even more certain that we will win. This is despite the fact that the odds may not have changed at all, before and after the act of ‘putting down money’ has taken place.

- We always rate our opinions and estimates as being correct and those of others as inferior. We refuse to be ‘actively open-minded’ and rarely if at all do we seek disconfirming evidence.

- We always overrate our power over the unknowns over which we never have any control. Hence, we tend to get surprised when things don’t work out as we expected them to. It is such a paradox that our behaviour as investors is something that we can control, but we don’t even try and do that since we are supremely confident that we are fully in control of our behaviour.

- When comparing our performance, we cheat and don’t see the numbers for what they are. We tend to give excuses and end up blaming everybody else, except the man in the mirror. That is a manifestation of our overconfidence bias. We refuse to see reality for what it actually is.

- We have a terrible time saying the words ‘I don’t know’. Humans are just not wired to say the three words ‘I don’t know’, but you’ll find great investors use it all the time. The more we know, the more we think we know even more than we do.

Net, net we are overconfident in our ability to overcome our overconfidence bias and all other biases that it results in! The combined effect of all of the above is that we end up taking risks that we shouldn’t take and inevitably that leads to under performance.

Martin Luther King Jr. was a black activist American civil rights leader who practised non violence and civil disobedience in the United States from 1954, until his death in 1968. In 1964 he won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequality through non violent resistance. With that back ground watch the video below:

Reasons for Overconfidence Bias

Messrs Brad M. Barber and Terrance Odean showed via their research that the Overconfidence bias is the result or combination of the following:

- Self Attribution Bias: our tendency to take credit for our success and blame others if we fail. Admitting our ignorance undermines our self-esteem.

- The illusion of control: our belief that can control the outcome of a situation or event by our actions. In reality, for the most part, and in a majority of the cases, we have no control over the outcome. But since we are under the mistaken impression (illusion) that we can control the outcome, it leads to complacent behaviour, which in turn causes a host of problems. Staring at stock prices is an example of an illusion of control; in reality, we have no control over what is essentially random. Another example would be so-called experts trying to predict the direction of the stock market. In other words, the ‘illusion of control’ is that uncanny feeling that we can exercise some influence over random chance events by our deliberate actions. For example, many of us feed our portfolios into some online tracking software and fool ourselves into thinking that by monitoring our portfolio in such a manner, we have some control over the returns. The illusion of control has been widely studied and researched. The following experiment was undertaken at Stanford University:

Researchers picked the names of stocks at random from the stock quotes. The volunteers to the experiment had a choice. Either they

(A) guess whether the stock will go up or go down on the next trading day

OR

(B) guess whether the stock had gone up or down on the previous trading day (you are not allowed to look at the stock price)

Two-Thirds of the participants opted to take choose (A). Why? That is because, in the case of option (B) above, the volunteers feel that the outcome is out of their control and in the case of option (A) they feel that they can somehow control the same. That is how the ‘illusion of control’ works.

As a result of the illusion of control, we feel that our decisions or choices are inherently better than the choices other people make for us. The illusion of control is widespread among investors. The risk is that when we believe we are in control, it makes us much more invested in our beliefs, choices and actions. As a result, we remain oblivious to the consequences thereof until it is too late.

- The Illusion of Knowledge: Since, we have a problem saying ‘I don’t know’, we do the next most stupid thing and that is to lie. We pretend to know more than we actually do. In some cases, the problem becomes chronic and at some point, we really come to believe that we do, in fact, know more than new actually do.

Blind Spot Bias

Many of us are aware of behavioural biases, but we firmly believe that these affect others and not you yourself. Its a foolish way of thinking and its called a bias blind spot. The question is do we have a metaphorical ‘blind spot’ as well? In other words, if not an actual blind spot, a virtual one? Research proves that we in fact do suffer from blind spots. Watch the videos below:

Selective Attention Test

The Door Study

Remedies for Overconfidence Bias

The best way in which we can confront our overconfidence bias is to stand in front of a mirror and ask the following questions:

- Am I the truly above average investor that I think I am? If that is true, by how much am I better or worse?

- Are my returns the direct result of my analysis and decision-making? What is the rate of return that I can achieve over the long-term? How does my historical performance compare with my peers and the benchmark averages?

- Am I following the correct process when taking an investment decision or am did I get lucky in spite of having a bad process? In other words, how much of my success or the lack of it is because of my investing process and how much of it is because of luck? In the investing world, the quality of the decision and its outcome are not always positively correlated.

- Do I know as much as I think I know or am I lying to myself?

- Teach yourself to say ‘I don’t know’ and ‘I don’t care’. In this way, you can circumvent questions about macroeconomics. Warren Buffett is famous for his quote saying that he has never taken an investment decision based on macro.

- At all times, keep asking ‘and then what’?

- Whenever you are faced with a question or have to opine on something ask yourself two questions: (a) is it knowable and (b) is it important? Build a ‘too hard’ pile for questions that cannot be answered based on these two and keep dumping things in the ‘too hard’ pile regularly; these are the stocks for which you can safely say that you don’t know, neither do you care.

- When we prepare discounted cash flows, we use discount rates and try and be conservative. Similarly, use an overconfidence haircut to trim all your estimates.

- Start writing a trading or an investing journal and fill it with all the details and your reasoning why you want to buy or sell the stock in question. Revisit your estimates after twelve months and check to see how accurate they were. Did you overestimate or underestimate the outcomes? You should not be looking at the stock price; you should be looking at whether your reasoning was correct. In other words, did the stock price rise or ebb for the reasons you thought it would?

- When we track our portfolios, we should be monitoring not just what we own, but also what we sold and even the stocks that we passed up on after analysing them.

- Always remember that staying wrong is far worse than being wrong. Embrace your mistakes and rectify them. Learn from your mistakes. The failure rate in the investing world is roughly 60 per cent.

- Always follow a rules-based process aka an investing checklist and don’t deviate from it. Use diversification to reduce risk.

- Always ask the question ‘why’. Ignore the day news, remember that the press follows the market action and not the other way around. Stop paying attention to forecasts.

What are Base Rates?

In statistics, the Base Rate is the probability by which change influences a phenomenon to a certain degree. The changed condition (or variable) determines the degree to which a variable will be affected and thus, changed.

‘Base Rates’ have different meanings depending on the context in which the term is used. In the banking industry Base Rates are also known as discount rates and refer to the interest rate at which the central bank lends money.

However, we are not concerned with this definition while studying Behavioral Investing. In so far as Behavioral Investing and decision making are concerned, Base Rates refers to the prior probabilities expressed explicitly in terms of the reference class which we are trying to forecast. Whenever we are taking a decision we are in an indirect manner making a forecast. Depending on what we expect the outcome of our decision to be, and the risk to the same, we decide accordingly. In other words, there is an element of forecasting in all our decision-making. As a result, what we do is to gather a lot of information, combine the information with our experience and arrive at a decision. The decision so arrived at has an element of forecasting embedded in it, even though we may not be trying to forecast.

For example, we may ask a home builder when the project will be completed or an economist for the expected growth rate for the economy. Depending upon who you ask, the answer to both these questions will vary. The problem with this methodology is that we are asking the wrong question. How can we expect to get the correct answer when we are asking the wrong question? In the example cited above, what we should be asking is: how long did similar projects take to get completed or how did economies perform in the past when similar conditions existed? That gives us probabilities a priori. In other words, the Base Rate is the answer to the question: ‘what is the experience of others who have faced similar situations?’ Once we do this, it occurs to us that other people might approach the same problem differently. In other words, using Base Rates helps us to understand that the range of possible outcomes is far wider than we could have ever imagined. Trying to arrive at probabilities using Base Rates is also known as ‘Reference Class Forecasting’.

Base Rate Neglect

Base rate fallacy, or base rate neglect, is a cognitive error whereby too little weight is placed on the base (original) rate of possibility. In behavioural finance, base rate fallacy is the tendency for people to erroneously judge the likelihood of a situation by not taking into account all relevant data.

Meet Preeti. She’s thirty-one years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. In college, Preeti graduated in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice and participated in climate change demonstrations. Before I tell you more about Preeti, let me ask you a question about her. Which is more likely?

a. Preeti is a bank teller.

b. Preeti is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Answer is a, most people think it’s b

Bank tellers who are also feminists—just like bank tellers who model or despise climate change are a subset of all bank tellers, and subsets can never be larger than the full set of which they are a part. In 1983 Daniel Kahneman, he of Nobel Prize and DRM fame, and his late collaborator, Amos Tversky, introduced the Preeti problem to illustrate what’s called the “conjunction fallacy,” one of the many ways our reasoning goes awry.

Another example would be the recommendations of experts on financial television. Sometimes we buy a stock because some expert on a television channel or some website recommended it. If the stock climbs higher, we conclude that the source is a good one. That is too hasty a conclusion to arrive at based on just one recommendation. To arrive at an opinion, we have to study all the recommendations over the last many years, something that almost none of us end up doing. Only then can we conclude whether the recommendation in question was the result of luck or was there some skill involved as well.

To illustrate further, while forecasting growth rates for a company or a sector, we should be asking: what is the historical growth rates for companies in this sector?.

What are stated above are examples of Base Rate neglect, which is all pervasive in the financial universe. Despite the fact that Base Rates are an extremely powerful tool for decision-making and forecasting, they continue to be heavily under utilised. There are two reasons why Base Rate neglect is omnipresent. These are:

- Using Base Rates means setting aside all the information and experience that we have gathered. In other words, we have to accept that our beliefs are subservient to historical precedents of a similar nature. Since we tend to hold our thoughts in high esteem, this is not a very easy thing to do.

- Base Rates are not easily available. One has to think about the reference class in question and then make a conscious attempt at finding the base rate for that class. Most of us are loathe to engage in the exercise.

How to use Base Rates

Base Rates are very useful depending upon how accurately we have combined our information with them. Using Base Rates in an efficient manner, there are two outputs that we can arrive at. These are (a) an estimate of regression towards the mean that might occur and (b) the correlation coefficient for our forecast.

Inside View v/s Outside View

Daniel Kahneman has written a very nice article on how he and Amos Tversky stumbled upon this behavioural phenomenon. The article is titled Daniel Kahneman: Beware the ‘inside view’. Kahneman’s analysis has helped in building forecasting models with greater accuracy.

What Base Rates do is that they move us from the ‘inside view’ to the ‘outside view.’ We have to ask a simple question: ‘how often does this happen?’ How often something has occurred in the past is a usually a good indicator of how often it will happen in the future. It is this kind of analysis that Base Rates force us to do. The outside view is how we view other peoples situations. Once we do this, we can extend the frame of reference and start looking for patterns. To start with we have to acknowledge an element of uncertainty when we take a decision and once we do that it helps us become more ‘open-minded’. We realise almost immediately that we can be wrong.

Let me illustrate:

- It is a known fact that India has one of the lowest divorce rates in the world. However, it is equally true that divorce rates have more than quadrupled in the last five years. Just suppose that the divorce rate was 10 couples out of every 1000 were getting divorced five years back, as on date 50 couples are getting divorced. In other words, the divorce rate has moved from 1 percent to 5 percent.

- When one of us gets married, we never think in terms of these probabilities being applicable to us. If we were to take into account the Base Rates for divorce in India, when we get married, we must accept that there is a 5 percent chance of getting divorced.

- In other words, we tend to ignore how often something typically occurs when we take personal decisions. We fail to acknowledge that the probability of something happening to everybody else applies to us as well.

How to distinguish between the Inside View and the Outside View?

- The inside view is how we view our situation based upon our experiences and intuition. It is a narrow view since it is limited to ourselves. In other words, the sample size is one. We all know that all humans suffer from Cognitive Dissonance and a host of other biases. Hence, the inside view is a limited and heavily biased view of the range of possible outcomes. It follows that the inside view should not be used for decision-making.

- The outside view is the view of the same problem but the sample size is everyone but ourselves. Since the sample size is large and representative, incorporating the outside view in our decision-making, invariably leads to better outcomes.

Skill v/s Luck

Success or failure for any businesses and career involves a combination of luck and skill. However, there is no consensus on the weight of each of these two elements in the ‘success equation’. Michael Mauboussin has addressed this conundrum in his book called ‘The Success Equation’ in a very eloquent manner. In his book, Mauboussin has said: ‘There’s a quick and easy way to test whether an activity involves skill: ask whether you can lose on purpose. In games of skill, it’s clear that you can lose intentionally, but when playing roulette or the lottery, you can’t lose on purpose.’ According to Mauboussin, the features that differentiate luck and skill are:

- Skill can be defined as ‘the ability to use one’s knowledge effectively and readily in execution or performance.’

- Luck can be defined as ‘events or circumstances that operate for or against an individual, over which he or she has no control.’

- Luck has three core elements: (a) it operates on an individual or an organisational basis; (b) it can be positive or negative and (c) it is reasonable to expect that a different outcome could have occurred. Skill, on the other hand, is process-based.

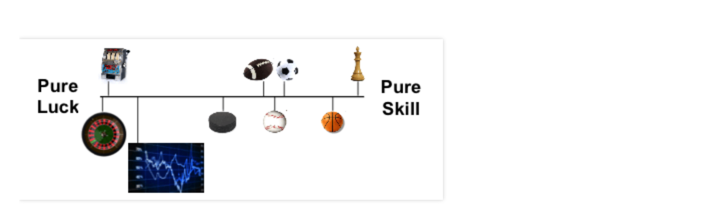

We need to understand where an activity falls on a continuum from pure skill/no luck on one extreme to no skill/pure luck on the other. For instance, running races are nearly all skill, the fastest runner wins; whereas roulette wheels are all luck. Everything else is somewhere between the extremities. Quantifying where your activity sits is enormously useful in assessing past outcomes and for making decisions about the future. In the book, Mauboussin has shown the continuum of vocations that are purely based on luck at one end and those that are dependent on skill on the other. Investing is closer to the ‘luck end’ of the continuum than it is to the ‘skill end’, as can be seen in the image below:

How can the skill v/s luck equation be used as part of the Behavioral Investing framework? The stock market is a complex adaptive system that has elements of both luck and skill. The continuum shown above can be overlaid with the function of time. In other words, luck holds sway over the short-term and skill matters more than luck over the long-term. The following are the key takeaways:

- We should not be using historical short-term performance metrics and extrapolating them over the long-term while taking decisions.

- Since the short-term volatility in the stock market is random and heavily influenced by luck, we should use Base Rates and probabilities for making forecasts.

- Over the short-term, even a good process can deliver a poor outcome and vice-versa.

Untangling Skill and Luck in Business

Skill v/s Luck – MindMaps

Correlation ≠ Causation

Correlation is a statistic that measures the strength of the relationship between two variables. Correlation Coefficients are used to define the same in arithmetical terms. Correlation coefficients can range from +1 to -1. A coefficient of +1 shows perfect positive correlation and a correlation of -1 shows a perfect negative or inverse correlation. In the case of positive correlations ranging from between zero and one, zero would mean that there is no correlation and one would signify perfect correlation.

When the correlation coefficient is closer to zero, outcomes will be determined more by luck than by the skill. Conversely, when the correlation coefficient is closer to one, skill will be the dominant force. The closer the correlation coefficient is to zero, the greater the weight base rates should be given while making a forecast (as against using your own judgement). Conversely, the closer the correlation coefficient is to one, we might be better off using our judgment.

Michael Mauboussin on Behavioral Investing

Hindsight Bias, Availability Heuristic & Representative Heuristic

Hindsight Bias & Outcome Bias

In the words of Daniel Kahneman: ’Hindsight Bias makes surprises vanish. People distort and misremember what they formerly believed. Our sense of how uncertain the world really is never fully develops, because after something happens, we greatly increase our judgements of how likely it was to happen’

We always tell ourselves that we knew it was going to happen and that we foresaw events as they actually played out. This feature of our personality is called the ‘hindsight bias’. What is so bad about hindsight bias is that we lie to ourselves thinking that we knew what was coming and worse still, we refuse to learn from our mistakes. Hindsight Bias is also known as ‘the I knew it all along’ phenomenon. Its another cruel trick that our inner conman plays on us. Once we know the outcome of an event, we tend to look back and believe that we knew what was going to happen right from the beginning. In other words, we tend too incorporate, almost seamlessly, the new piece of information into what you already know. Take the example of bitcoin, almost every one will now claim that they knew it was going to crash. When we hear something, we automatically incorporate it into something we already know; in the process we distort and misremember what we formerly believed. Effectively, after the outcome of an event has taken place, we increase our judgment of how likely it was in the first place. Hindsight bias has a deleterious effect on us because once we believe (and we really do believe) that the past was predictable, it makes us even more confident in our forecasts about the future. Unknowingly, we are also distorting our memory which is highly avoidable.

While investing, after demonetisation took place in November 2016, most investors were skeptical about India’s economic growth. The stock market was taken by surprise and it corrected by roughly ten percent. Not many investors were willing to invest. Now after the market has gone rip by thirty percent, everyone and their great-grandmother claims that they always knew that, post demonetisation was a great time to invest. Its the ‘I-told-you-so’ or ‘I-knew-it-all-along’, phenomenon.

Closely related to the hindsight bias is the Outcome Bias, whereby we start judging the quality of a decision after the outcome is known. In Poker this is known as resulting.

Availability Bias

Availability Bias is the tendency of being influenced by what is recent or readily available. Just because some information is readily available it does not mean that it should be used while taking a decision. More often than not, it is what most of us do. We don’t even try and understand the odds or the probabilities but rely on whatever information is readily available. Availability Bias is the bias whereby we believe something is more likely just because it is easier to remember. In other words, the more comfortable something is to think of, the more we feel that it is right and vice-versa. More often than not, if we have experienced something, we believe that it is the real thing and that there aren’t any other alternatives. We are biased in favour of information that comes immediately to our mind or is presented to us as opposed to what might be the more representative or the correct set of data. For example, by watching the daily news, it is easy to get the impression that there is nothing right in the world since what gets highlighted is all the bad stuff and none of the right thing. Effectively, the mere availability of data is resulting in a change in our behaviour. More often than not, the mere availability of information tends to nudge us in the wrong direction. Hence, it is effortless to fall for our Availability Bias, and one has to stop and think in probabilistic terms to get away from being trapped by it.

Action Bias

Many times in investing it makes sense to just do nothing. Ironically, that is one of the most difficult things for humans. As someone has famously said: “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” This finding is called Action Bias and the initial research was done by studying the goal-keeping “Action Bias Among Elite Soccer Goalkeepers: The Case of Penalty Kicks”. The researchers made the case that just doing nothing i.e. not diving to either sides and standing idle was a more effective method for saving goals. In other words, the chances of stopping the ball were highest when the goalie stayed in the centre. Why then do goalies dive? The reasons attributed were (a) they want to show that they are doing something (social proof) and (b) the goalie genuinely feels that he can stop the ball by diving. In the event that a goal is scored with the goalie standing idle, the media would probably massacre him or her for inaction, even though it is scientifically proven that it is the best thing to do.

How is the above related to Behavioral Investing? It is exactly what happens in the investing world. Most money managers, seem to be buy and sell at the worst times, when, in fact, the best thing to do is to sit on your hands.

Do / Say Something Syndrome

The Do / Say Something Syndrome is an offshoot of the Action Bias described above. With the advent of the internet, our inherent bias at wanting to do and say something has been accentuated. Plato, the famous Greek philosopher, has said:Wise men speak because they have something to say; Fools because they have to say something.

In the words of Charlie Munger:

And here my favourite thing is the bee, a honeybee. And a honeybee goes out and finds the nectar and he comes back, he does a dance that communicates to the other bees where the nectar is, and they go out and get it. Well some scientist who is clever, like B.F. Skinner, decided to do an experiment. He put the nectar straight up. Way up. Well, in a natural setting, there is no nectar where they’re all straight up, and the poor honeybee doesn’t have a genetic program that is adequate to handle what he now has to communicate. And you’d think the honeybee would come back to the hive and slink into a corner, but he doesn’t. He comes into the hive and does this incoherent dance, and all my life I’ve been dealing with the human equivalent of that honeybee. [Laughter] And it’s a very important part of the human organisation so the noise and the reciprocation and so forth of all these people who have what I call say-something syndrome don’t really affect the decisions.

Basically what Munger is highlighting is our confusion of activity with results. We are wired in such a way that we feel that more action will result in better or improved outcomes. Being careful, cautious and patient sounds sensible, yet it is something that is very difficult to achieve in the ‘heat of the moment’. We need to model our behaviour and our reactions in the following manner:

- As investors, we inherently feel the need to react to everything and anything that is happening. Inadvertently, we equate action with effectiveness. As a result, when there isn’t enough clarity, as is often the case in the markets, we cannot see things clearly enough. We need to remind ourselves that what we are seeing, might be the opposite of what the reality is. Moreover, acting in the absence of clarity increases the probability of being wrong. Effectively, we end up offering an emotional response and take decisions in the heat of the moment. At all such times, when sanity returns ergo clarity emerges, we invariably regret any such decisions. It makes sense to procrastinate or ‘wait’.

- At all times when we offer emotional responses, at some later stage we ask ourselves the question: ‘What was I thinking or how could I have done this?’. More often than not, the answer is that when we responded emotionally, we weren’t thinking; we were allowing our emotions to dictate our actions.

- Before taking a decision that is based on an event or occurrence, we need to ask the question: ‘and then what?’. It helps us to think and look for answers to the repercussions of the event in question.

- Many a time, we offer unsolicited advice or opinions when we have not been asked for the same. At all such times, it makes sense to do or say nothing instead. We need to ask ourselves the following questions: (a) will expressing ones opinion help the outcome?, (b) am I qualified to opine on the matter, or subject? and (c) does it make sense to shut up?

- One of the most common behavioural traits is our tendency to react to official economic reports and statistics that are broadcast by government agencies or other data collection agencies. We need to remember that these pieces of data while being important, seldom have any bearing on the price action. For the most part, markets have moved ahead of the reports, and as long as the data does not contain any surprises, there is little point in acting ex-post. Since markets are forward-looking, they discount economic activity as it happens and don’t wait for the ‘official data’, which is backward looking. In other words, while investing, we have to keep looking in the windscreen and not in the rearview mirror.

Conclusion

The most critical and common Cognitive Biases are listed above. There are more than two-hundred known Cognitive Biases. Many of them overlap or are off-shoots of the ones listed above. While knowledge of Cognitive Biases is imperative to understanding Behavioral Investing, knowing how to combat them is even more important. Charlie Munger has via his various speeches shown that thinking is a critical part of our decision-making process. It follows that we can become mindful (and not mindless) if we can ‘think things through’. Hence, we need to know, how to think. Some wise man has rightly said, ‘there is nothing either good or bad, thinking makes it so’.

Even though thinking is critical for effective decision-making, we end up doing very little of it. Almost all of us tend to act first and think later. It follows that most of us manage to fool ourselves from time to time, to keep our thoughts and beliefs consistent with what we have already done or decided. As Kahneman has stressed, our impulse (system 1) tends to act first and our reasoning (system 2) follows our impulse. Unintentionally, what System 1 does for us is to provide us with a repertoire of biases. What these biases tend to do is to reduce the decision-making making stress for us. Kahneman calls these heuristics, and they are the correct way to respond in a majority of the instances, except that they are wrong at other times. The reality is that we wouldn’t be able to navigate in life without these heuristics or mental shortcuts. What we need is a way or a method to control our biases; we need a kind of a speed breaker to our thought process. In other words, we need the prejudices, but we only want the right ones, and we want to be relieved of the troublesome ones. What we need to do is to train our System 1 to develop better habits.

Charlie Munger on Cognitive Biases

Munger has waxed eloquent on Cognitive Biases and has highlighted the fact that we are reluctant to change. In his words:

“The brain of man conserves programming spaces by being reluctant to change. The relationship between the human brain and an idea is like a human egg with a sperm. Once an idea gets into the brain, other ideas are prevented from entering by a shut-off valve, just like an egg does to additional sperm once one gets in. In other words, what you think will change what you do, but perhaps even more important, what you do will change what you think. And you can say ‘Everybody Knows that’. I want to tell you that I didn’t know it well enough early enough”.

What Munger is saying that we should reverse that process; think first and act later. In other words, Munger is teaching us how to be ‘Mindful’ instead of being ‘Mindless’. Since our avowed objective is to think first and act later, it follows that we need to know, ‘how to think’. Although Munger’s words (italicised above), are so important, their significance is grossly understated. If you re-read the above sentence, and ‘think’ about it, the ramifications of how profound it is will be crystal clear. It follows that the importance of ‘thinking’ as a process cannot be understated. Hence, we need to learn how to think.

How to Think

What is ‘thinking’? In the real world, thinking is not the decision itself, but what goes into the process of making a decision. The assessment, weighing the evidence, making sense of the data, speculating about the pros and the cons, using probabilities (not possibilities) before concluding, are all part of the ‘thinking process’. Most of the time, making a decision involves predicting future outcomes. In a world of unknown unknowns, predicting the future is difficult and trying to time it is next to impossible.

Thinking is an art and not a science. Somewhere, deep inside our minds, we are reluctant to think and tend to avoid it as far as possible. Thinking is slow, requires patience, is hard, and tiring, all at the same time; that’s why we do so little of it. Since thinking is an art, it is resistant to a strict set of rules, neither can one prescribe any do’s and don’ts for the thinking process. Alan Jacobs has written a book called ’How to Think: A Survival Guide for a World at Odds’. I’ve tried to distil the wisdom from the book into the following Nine points which can be used as a checklist for engaging in the ‘thinking process’.

- Instead of being impulsive, take five minutes before reacting. Examine your emotional responses. Before our impulses take over, try and imagine a situation where the roles between you and the other person are reversed; its called ‘method acting’. As some wise man has said: ‘do to others what you would have them do to you’. Once we engage in ‘method acting’, what we have to do is, for five minutes, in our mind, we have to speak someone else’s thoughts and for those five minutes, stop advocating our own. Religiously implementing the five-minute rule is almost guaranteed to improved decision-making.

- Seek out thoughtful people who disagree with you, but are rational thinkers. At all times, remember that we may be wrong about something. Being open-minded means that one has to be willing to re-examine one’s assumptions, and at the same time engage in civil discourse. If we do conclude that we are wrong, we should not stay wrong. Staying wrong is far worse than being wrong. Course correction is critical, and we should cultivate the ability to change our minds.

- Don’t argue to win, argue to learn. When engaged in debate, try and establish what the other person is trying to say, understand what the argument is all about. Try and differentiate your interpretation of the case with what the other persons mean to say. Most of the time, debates are just glorified communication gaps and highlight the difference between what is mentioned as against what is intended.

- Hear what others have to say and think over what is being said. There is a difference between ‘hearing’ and ‘listening’. Someone has rightly said, ’hearing is through the ears and listening is through the mind’. Most of us tend not to hear what is being said. In that case, the question of thinking does not arise. We cannot think if we don’t hear what the other person is saying. There are a couple of reasons why we are such bad listeners. These are (a) we love to talk and don’t want to give the other person an opportunity to do so, (b) we have an inherent bias against the person who is speaking, (c) we multi-task and don’t pay attention to what is being said, (d) we are impatient and frequently interrupt the speaker instead of letting him, finish speaking and finally (d) our ego comes in our way of being good listeners because we are reluctant to change. Listening is difficult, and one has to work towards being a good listener. Being a good listener is showing respect for the other person. It is imperative to the thinking process.

- Once we have heard the other person, always try and see if he or she is trying to divert our attention and preventing us from seeing something that is important. If someone is trying to sensationalise some event or action, be careful while forming judgements. It is often true while dealing with persons who have a loud voice or are unduly aggressive. Try and gravitate away from such individuals. Associating with the correct people will encourage thinking with the best. If one were to associate with undesirable elements, their thoughts tend to affect ours negatively. That’s why it is said that ‘you are known by the company you keep’.

- Avoid people who fan flames. If your peers demand you weigh in, ponder your choice of peers. Don’t feel you have to weigh in on every topic. Embrace the power of ‘I don’t know’. In the information age that we live in, everyone knows a little bit about everything. Warren Buffett has famously said: ‘I don’t worry about what I don’t know. I worry about being sure about what I do know.’

- Start writing a journal or a diary. Journaling as it is now popularly called, forces us to write what we think. Pencilling our ideas brings clarity to our thought process. Moreover, writing forces us to think. A significant upside of writing a diary is that we can revisit our thoughts at a later date and see what we got wrong (and why), or how we got things right, as the case may be. If we were right, we could repeat the same process in the future, and if we were wrong, we know how and why.

- As part of the thinking and journaling process, we ask ourselves a lot of questions and proceed to provide the answers to the same. Hence, to start with, we must be asking the right questions. Having done that, we must guard against our minds (System 1) playing tricks with us. Often, we substitute and proceed to answer an easier question, than the one that was asked. This process is known as ‘Question Substitution’. For example, we substitute the question ‘Is this fund manager skilled?’ with the question ‘How has this Fund Manager performed over the last three years?’. In the stock market, performance is a very poor and noisy proxy for skill, yet almost everyone seems to rely on it.

- Have the courage of your convictions and once you have ‘thought things through’, dare to act on your thoughts without getting distracted by the ‘noise of social media’. Social Media, inadvertently tends to replace our thoughts with our emotions. In other words, we have to develop an attitude of ‘not caring’ about other peoples opinions. Once we get distracted by social media, we are indirectly invested in ‘not thinking’.